One of the responsibilities of the Technical Coordinator in the Ohio Section is to submit something for the Section Journal. The Section Journal covers Amateur Radio related things happening in and around the ARRL Ohio Section. It is published by the Section Manager Scott – N8SY and articles are submitted by cabinet members.

Once my article is published in the Journal, I will also make it available on my site with a link to the published edition.

You can receive the Journal and other Ohio Section news by joining the mailing list Scott has setup. You do not need to be a member of the ARRL, Ohio Section, or even a ham to join the mailing list. Please sign up!

If you are an ARRL member and reside in the Ohio Section, update your mailing preferences to receive Ohio Section news in your inbox. Those residing outside the section will need to use the mailing list link above.

Updating your ARRL profile will deliver news from the section where you reside (if the leadership chooses to use this method).

Go to www.arrl.org and logon.

Click Edit your Profile.

You will be taken to the Edit Your Profile page. On the first tab Edit Info, verify your Email address is correct.

Click the Edit Email Subscriptions tab.

Check the News and information from your Division Director and Section Manager box.

Click Save.

Now without further ado…

Read the full edition at: http://arrl-ohio.org/news/2018/OSJ-Apr-18.pdf

THE TECHNICAL COORDINATOR

Jeff Kopcak – TC

k8jtk@arrl.net

In all the ragging (er, discussion?) on Windows 10 last month, Bill – K8RWH had some good points and questions about Linux that I decided to write a follow up this month. There is a lot to parse, especially different terminology. The most useful website for Linux information is called DistroWatch, short for Distribution Watch. Most of the information here will come from that site. Let’s get to it.

History

Linux came out of the Unix operating system implemented by Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie (both of AT&T Bell Laboratories) in 1969. “Linux began in 1991 with the commencement of a personal project by Finnish student Linus Torvalds to create a new free operating system kernel. Since then, the resulting Linux kernel has been marked by constant growth throughout its history. Since the initial release of its source code in 1991, it has grown from a small number of C (programming language) files under a license prohibiting commercial distribution to the 4.15 version in 2018 with more than 23.3 million lines of [code] … ” (Wikipedia).

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the official Linux mascot. “Torvalds announced in 1996 that there would be a mascot for Linux, a penguin. This was due to the fact when they were about to select the mascot, Torvalds mentioned he was bitten by a little penguin on a visit to the National Zoo & Aquarium in Canberra, Australia. Larry Ewing provided the original draft of today’s well known mascot based on this description. The name Tux was suggested by James Hughes as derivative of Torvalds’ UniX, along with being short for tuxedo, a type of suit with color similar to that of a penguin” (Wikipedia).

Crash course in Linux terminology

GNU/GPL – software licensing methodologies frequently used by Linux and Unix variants.

Open Source – anyone can see the building blocks of a project known as the source code. This is beneficial because anyone with skills can fix and improve upon an open source program.

Kernel – is the core to any operating system (not only Linux). It interacts with and controls the computer’s hardware (mouse, keyboard, monitor/graphics, hard drive, USB devices, network). It is the lowest level of the operating system.

Operating System – collection of kernel and software that make a computing device work. Most operating systems include drivers, text editor, file manager, and a method for installing & removing applications (known as a “Package Manager” in Linux).

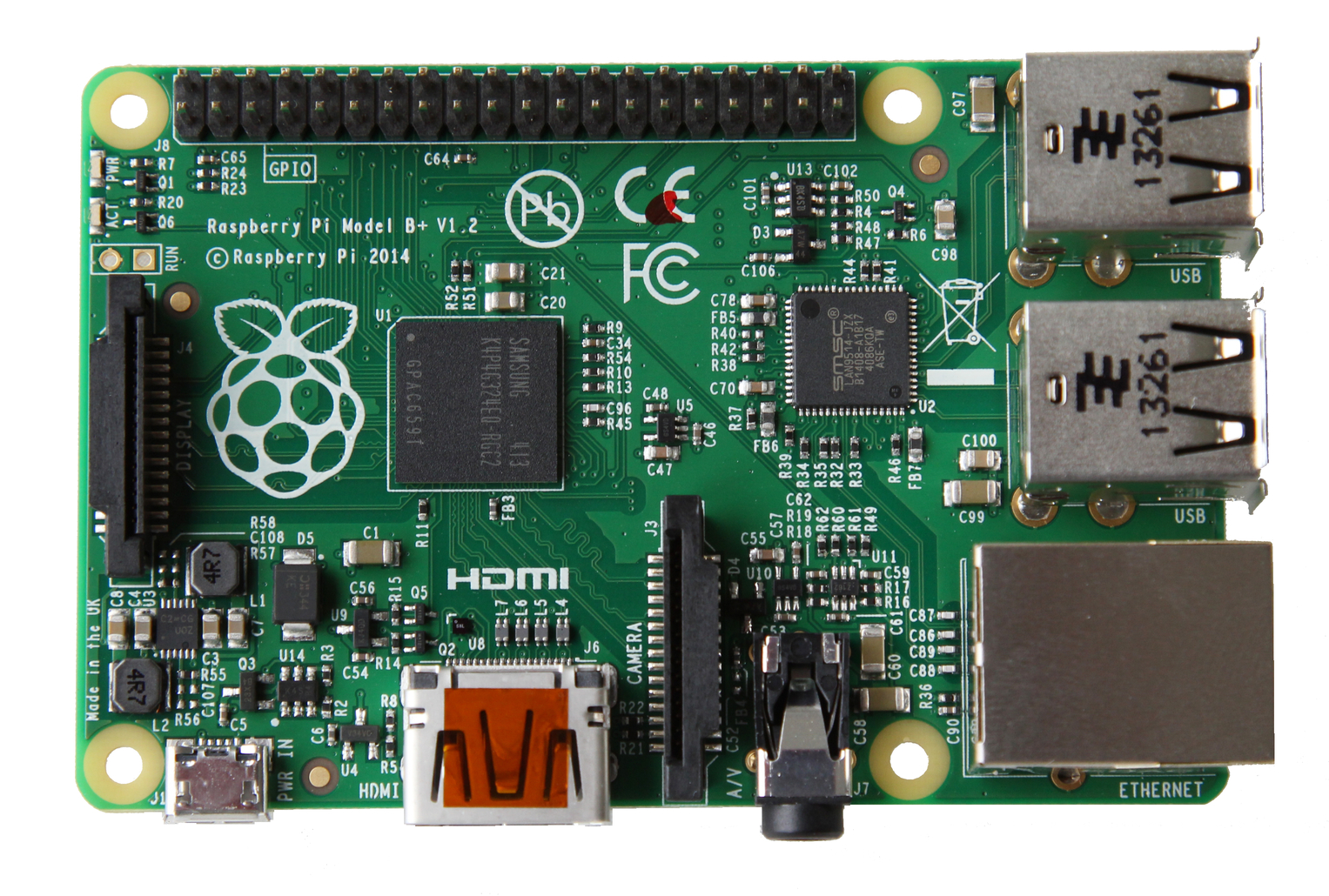

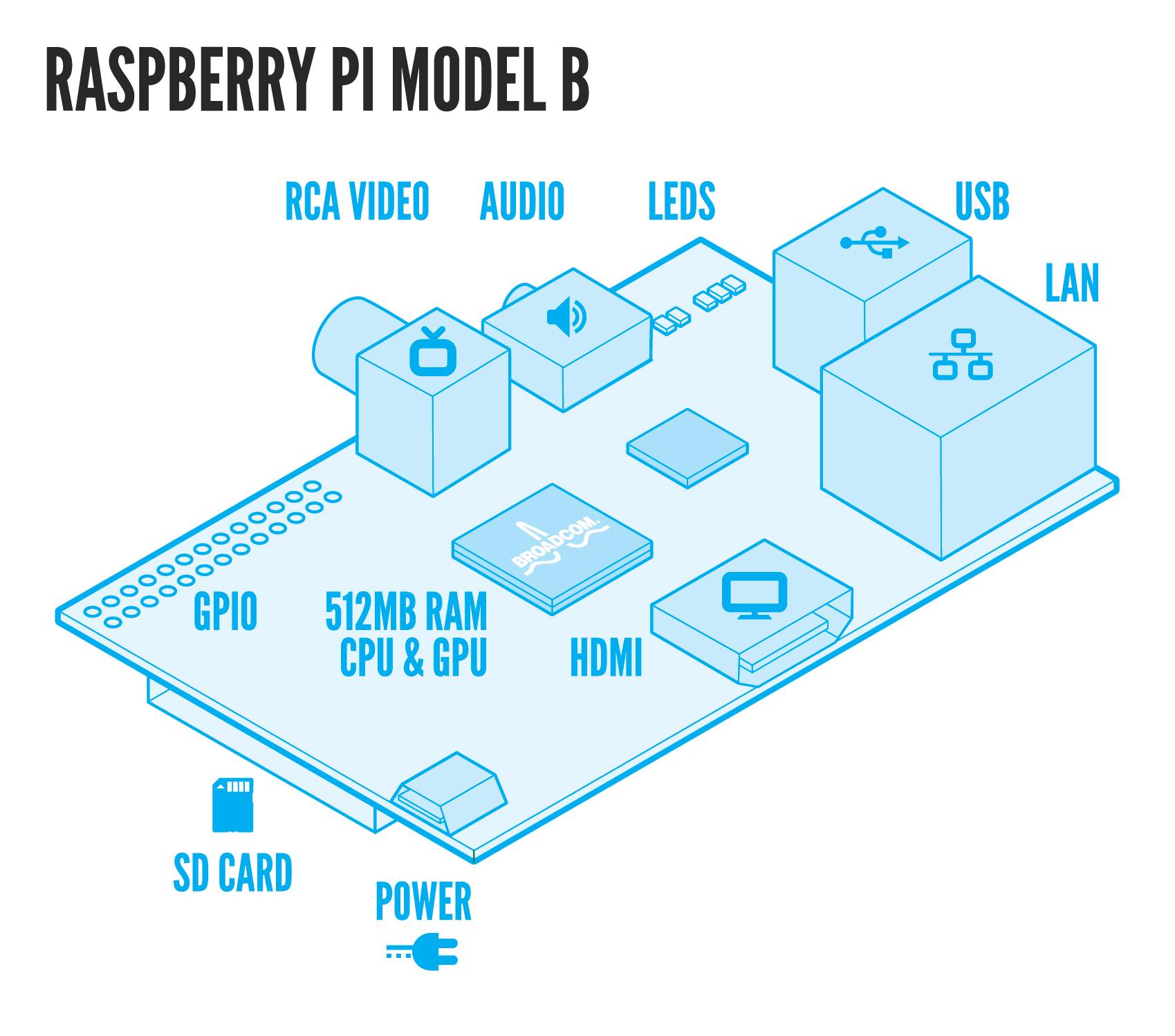

Architecture – type of processor an operating system can run. 64-bit, 32-bit processors, Raspberry Pi and mobile devices are examples.

Live CD/Medium – the operating system can be run from a CD or USB drive without installing to a hard drive. This is useful in testing different operating systems or to aid in recovering an inaccessible system.

Dual-boot – in contrast to “live CD,” installation of one or more operating systems on the same computer. My experience: install Windows first, then Linux. The Linux boot-loader plays nice with Windows but not the other way around. Reinstalling Windows will also break the Linux boot-loader. It can be repaired but will stress your Google and command line-fu skills.

Distribution – similar to “Operating System” but often targeted for a specific purpose or category: servers, desktops, beginners, education, gaming, multimedia, security, utilities, telephony, etc.

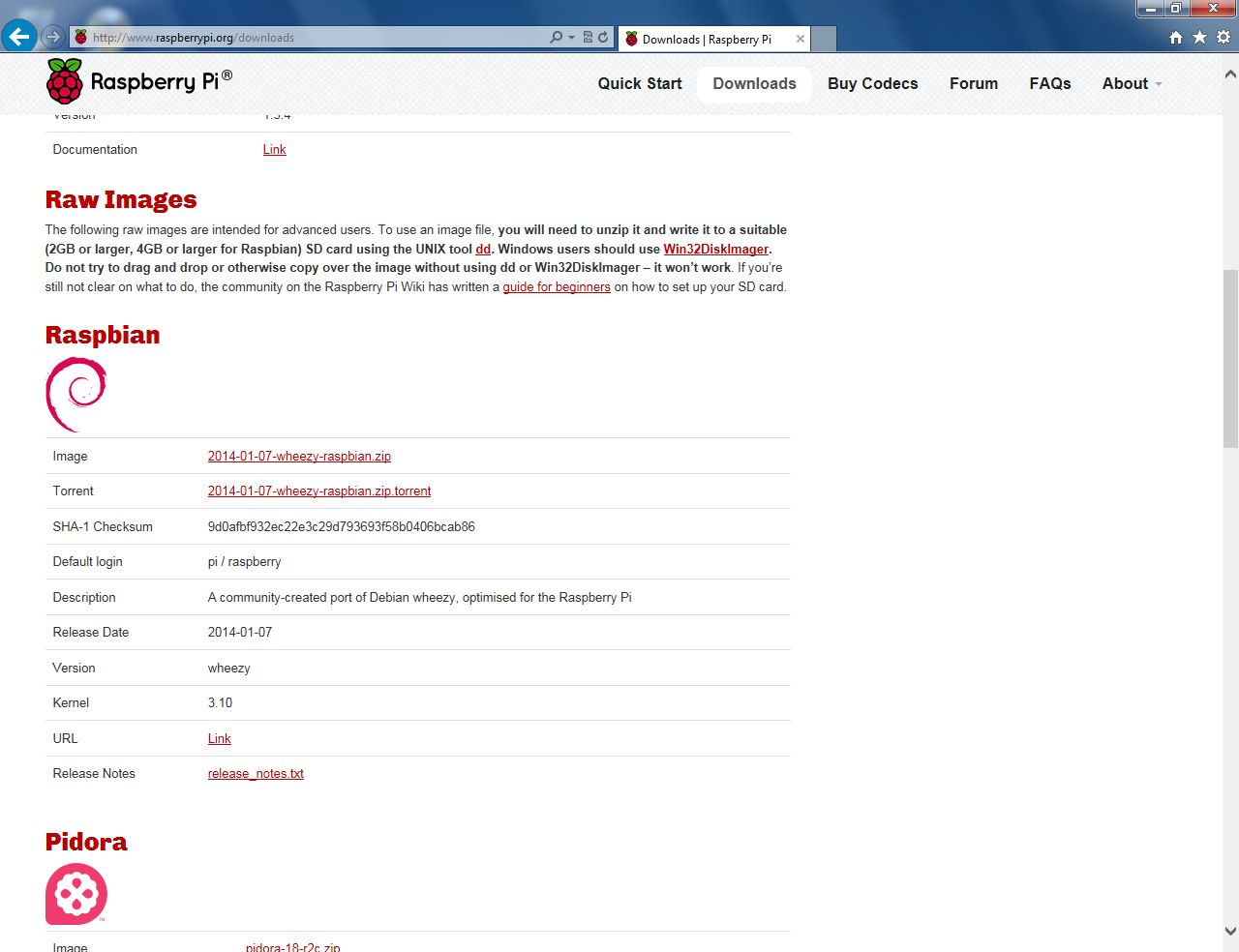

Checksum or Hash – applies an algorithm to data. It is used to track errors introduced in transmitting data or storing data. Checksum programs are standard in Linux operating systems. A third-party program like HashTab or QuickHash GUI are needed to verify a checksum in Windows.

Desktop environment – how a user interacts with multiple applications at once. This is a matter of personal preference. Popular desktop environments are: Cinnamon, GNOME, KDE, MATE, and Xfce.

Popular Linux Distributions

DistroWatch has just short of 900 Linux distributions in their database. Over 300 are considered active (updated in the last 2 years). Only about a handful are useful to average users. For a complete guide see “A Guide to Choosing a Distribution.”

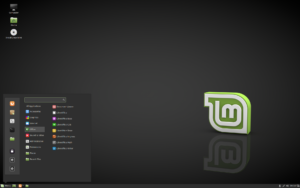

Linux Mint – launched in 2006 to address many of the drawbacks associated with a more technical operating system such as Linux. Using the Ubuntu distribution as a base, many beginner enhancements were created for usability. I had read about security concerns with Mint and began to steer users away from it. However, DistroWatch published a “Myths and Misunderstandings” debunking many of those points. If you’re a noobie and want to dive into Linux as an alternative operating system, start with Mint.

Ubuntu – Launched a few years earlier in 2004, this project took off faster than any other distribution and was touted as the way to get average people to use Linux. Learning from the mistakes of other projects and taking a professional approach to its users made it a popular choice. Excellent web-based documentation and an easy to use bug reporting facility was created. Though frequent major changes and the Unity interface – more suited for mobile devices – have driven users away.

Elementary OS – This one is for Mac users. It emulates MacOS and puts a lot of focus into ascetics.

Debian – base for the above and 120 other Linux distributions. Debian is remarkably stable due to its high level of quality control. It has support for many software packages and processor types making it a great choice for older systems. Due to that level of processor support it lacks newer technologies.

In the 300 other active Linux distributions, specialized versions serve an intended purpose:

- Network attached storage (NAS): NAS4Free, FreeNAS

- Disk, recovery, and utilities: GParted Live, CloneZilla, Knoppix

- Firewall: FreeBSD, pfsense, VyOS

- Forensics and security: Kali Linux

- Gaming: Lakka, LinuxConsole

- Older PC: antiX, ReactOS, Puppy Linux

- Incognito and anonymity (useful on the hotel provided “business center” PCs): Tails

Windows Compatibility

Users who’ve switched to Linux or Linux users that need to run a Windows app might ask: can I run Windows applications on Linux? Yes, there are a couple ways to accomplish this.

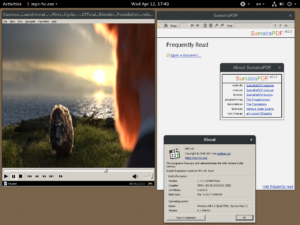

Run a virtual machine program like VirtualBox. A virtual machine emulates hardware and the functionality of a physical computer. Similar to dual-booting it requires a full installation of the desired (guest) operating system. Emulation is resource intensive for the physical (host) operating system hardware. It doesn’t make much sense to have a multi-gigabyte Windows virtual install to run a small application.

This is where WINE comes into play. Wine stands for Wine Is Not an Emulator. It’s not a virtual machine but rather a compatibility layer to translate Windows system calls into Linux system calls. WINE takes a considerable amount of configuring but programs like PlayOnLinux and Winetricks make life much easier. Neither solution is perfect and won’t succeeded in cases of complex applications or ones requiring specialized hardware.

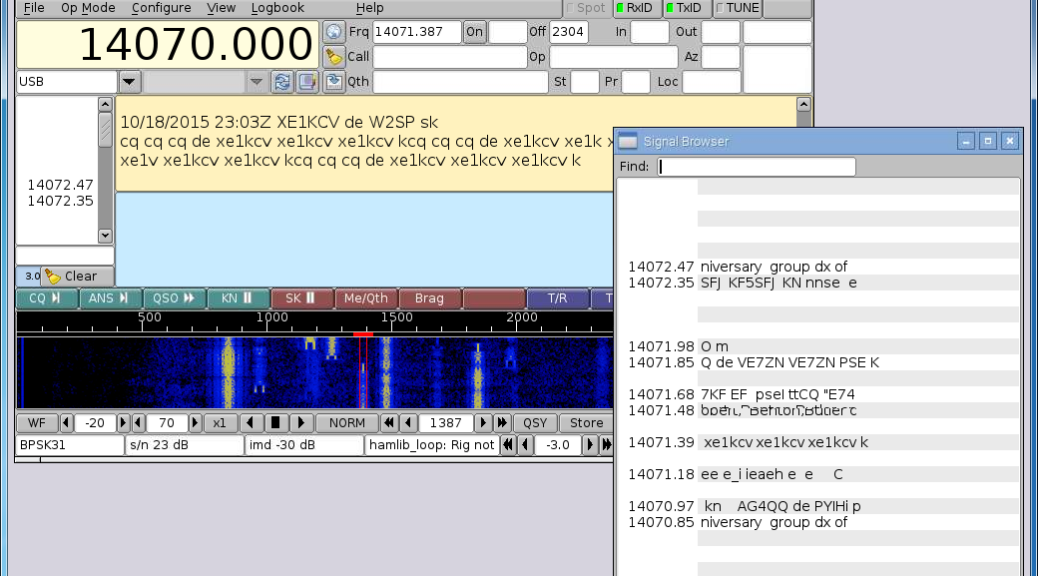

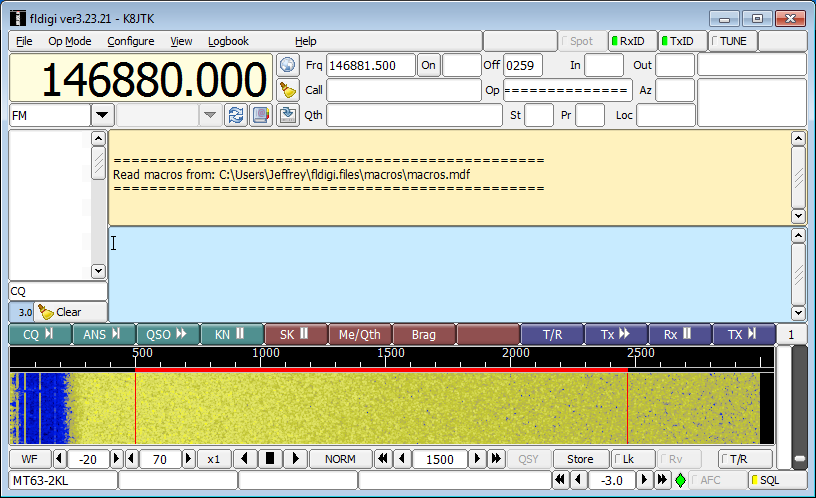

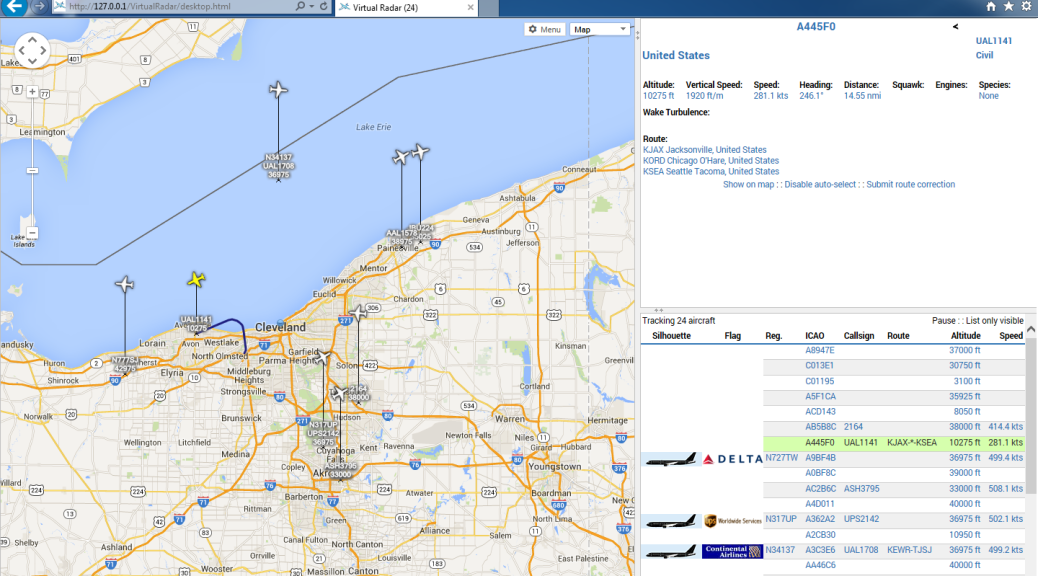

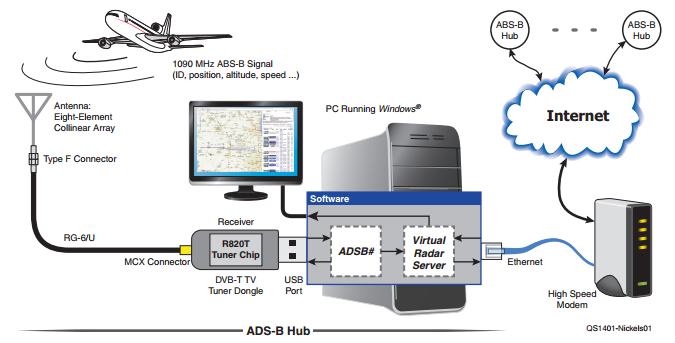

In terms of ham radio, Windows was the overwhelming platform of choice for Morse Code and digital mode applications because everyone was using it. Older Windows only applications (MMSSTV, DigiPan) are going to run well on that platform. The good news is programs like Fldigi and QSSTV are viable replacements on Linux and, in many cases, better than their dedicated Windows counterpart. In addition, the Ubuntu package manager has an entire category dedicated to Amateur Radio applications. If you’re someone whose fed up with the badness and frustrations of Windows 10, give Linux a try.

Thanks for reading and 73… de Jeff – K8JTK